I’m making my debut in conference workshops this May, on the 27th, in Runö at Let’s Test. Here are some thoughts I’ve put together about the process of making this workshop and its purpose.

Why I created this workshop

I spent a while thinking about my testing skills: how I could evaluate them, and how I could trace their evolution.

A big motivation to think about all that was, surprise-surprise…holding presentations. First, Maaret Pyhäjärvi invited me, at the end of 2013, to speak at a conference in Finland – Tampere goes Agile – , where I chose this theme, later on I applied with a presentation on this subject at CAST in 2014 and got accepted, and I subsequently applied to speak at CopenhagenContext in 2015. So this gave me a time span in which I was motivated to look further into my testing skills and their evolution. Although I had given attention before to how I use my skills and what my skills are, I found that having a deadline and a clear goal was helpful in keeping me interested and working on this subject.

And no, doing work for the presentation the first time did not mean that I was done with thinking about it. It’s actually been very interesting to see how my focus shifted and how each presentation work was a new piece in the repo of this subject. It was cool to trace back my former thoughts and approach on this. Some things were persistent, others were quite different.

Once I have gone through the experience of the presentations, I got the idea to explore this theme further in a workshop. So I started work on the “Examine your testing skills” workshop.

I created this workshop because I was curious about how other people reflect on their skills, and how they identify them. I was also curious how others would organize them into categories. After observing myself, I thought there was a lot to learn from looking at different approaches.

Apart from satisfying my curiosity, I also worked on this workshop because I thought it could be useful for the participants. In what way, though?

I am aware I cannot control what people learn. And as I thought of my goals with this workshop, some lyrics from one of Bjork’s songs was humming in my head: “I thought I could organize freedom – how Scandinavian of me”. Now, I’m not Scandinavian. I would say I’m more Balcan, if I relate to my geographical location and legacy, which suggests traits of operating in chaos instead of trying to organize it.

The challenge for this workshop was to provide a structure for observing skills and reflecting, while giving flexibility to participants in terms of what skills to focus on and what categories they create for them, so that they would be meaningful for their context.

How I created the workshop structure

I stumbled upon the difficulty of identifying skills when I was working on the presentation, and I tried to locate individual skills and analyze them. That didn’t work very well, because when trying to solve a problem I was working with more skills, not a single one. And the way I combined these skills together was contributing to solving the problem. So it proved challenging to follow one individual skill across multiple situations and to draw conclusions in terms of how I was using it and if it was effective.

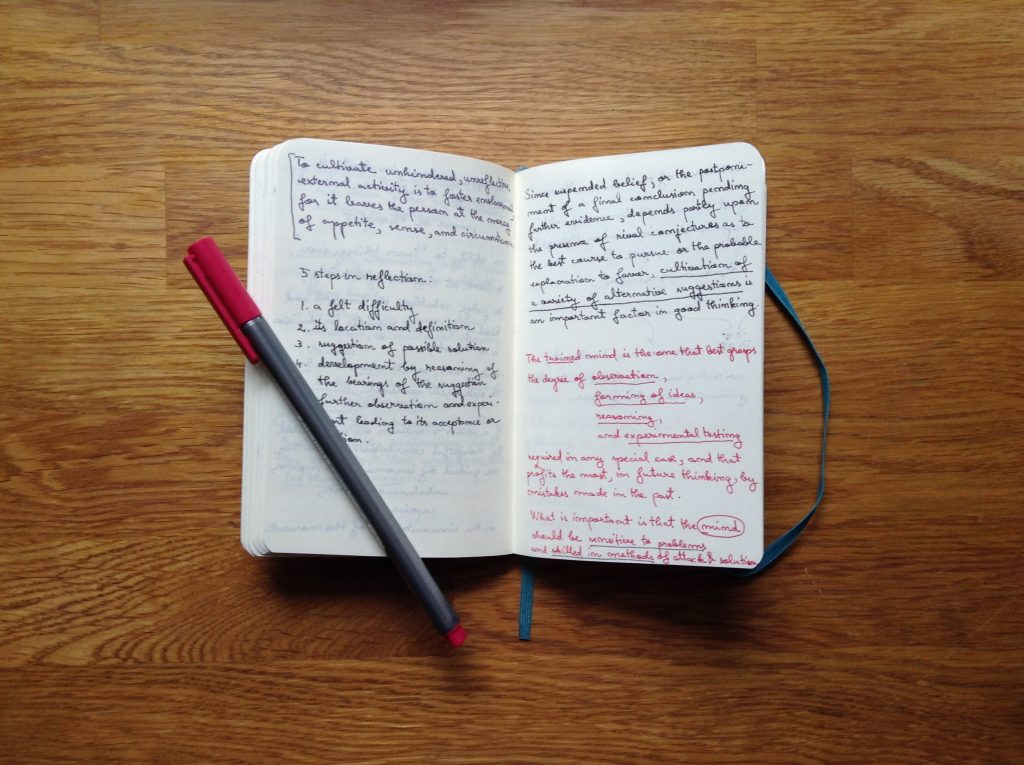

I later chose to examine my skills by looking at different situations and creating an inventory of the skill combination I used. I would then draw conclusions in terms of how that skill combination worked for me and think what could be tweaked in a similar situation for my skills to work better together. Only after this exploration I would find categories for the skills I had gathered on my list, to organize them somehow.

This could tell me, for example, if I focused a lot on certain types of skills and not so much on others. Or if I recently did not use skill categories I used in the past a lot. Or I could analyze similar situations to understand if I was consistent in my skills or if sometimes I used different skills when approaching the same type of problems. I would later on think what all these might mean. So this is the level of organizing I was working with.

I wanted to use this skill examining process in the workshop as well. Starting from the hypothesis that people would solve problems by using a combination of skills, it made sense to observe how those skills are used in a real problem-solving situation, analogue to one encountered in testing work. So in the workshop I am providing participants with problems to solve, and I am giving them the opportunity to tackle those problems, alternating problem-solving and reflection sessions.

I realized that although I am trying to build a model of reflection in regards to skills, the workshop was not so much about organizing this process in a template, but about providing an environment and an opportunity for reflection. So the exploration of one’s skills is centered around problem-solving, but not constrained by a template that would suggest that all participants should do it the same way, or use a similar set of skills. This is why problem-solving techniques are not listed in the workshop, as different people may be using different approaches and thus different skills when trying to solve a problem. My hypothesis here is that participants are comfortable or willing to approach a problem using a strategy they create themselves, not one provided for them.

The categorising process is also included, but it is not more granularly imposed, meaning that participants decide how they create their own categories.

Ladies and gentlemen, Reflection enters the stage

I chose reflection as the main focus of the workshop, because it is the main tool we will use for examining skills. There are two central aspects of reflection which I thought relevant to consider when employing this tool:

- For me reflection is first and foremost about noticing. And that’s something we most know already how to do in principle, right? Although we notice stuff every day as humans and particularly as testers, I personally found it effortful and non-trivial to make a habit of noticing specific things. I found this out by trying to do it. When trying to analyze myself in different situations and gathering information about my skills, I did a lot of re-thinking of my conclusions and ideas. It seemed very difficult for me to understand if they were useful and true, or some invention of my mind that was far from reality. So I wanted to explore with participants how we notice things around us, what kinds of things each person notices, and what they might have missed.

- Reflection can be more descriptive or more deep/critical. It seems that doing descriptive reflection is a good starting point, but deep reflection seems to be a more subtle skill and to lead to more insight about skills, since it can give more information about what could be different in one’s problem-solving process. This is why the workshop exercises strive to guide participants towards deep reflection.

Practicing reflection deliberately helped me realize how little I was actually noticing about myself. For example, I once did some very simple exercises in a sports class. One of the exercises we did was to simply observe our own breath. Not try to control it, or change it, but notice our rhythm, notice the air which we inhale and exhale, notice the parts of the body which were reacting to this activity. Another exercise was to notice which muscles I use when I keep my balance in a vertical position.

That sounds easy, but it was a good concentration exercise and damn hard not to alter my breathing when I was focusing on it, or my position when I was focusing on my balance point. I also noticed how granular noticing can be. When looking at a person who simply stands, you can notice that they are doing nothing. You can also notice small moments of imbalance. If you are that person, you can notice how your center of mass changes from moment to moment. You can notice how many small movements you actually make when you are standing, in how many directions, which are the factors that create those movements, how your muscles react to them to keep you still, etc. So there were a lot of dimensions to notice in these straightforward, simple situations.

Now when I think about an activity I do when testing, it gets a bit more complicated, because solving problems involves a lot of thoughts and decisions I make, so the activity is not as palatable and easy to decompose and analyze. This suggests that doing deep reflection and noticing relevant aspects can be quite challenging. With this realization, the fun begins. How do you do that? How do you simply notice what you’re doing? Then how do you follow the string of an activity? Then go beyond that isolated activity in your reflection, take a step back to view it from various perspectives, or compare and contrast it with other ones, consider the effects of that activity, and look for alternatives.

Creating a habit and the purpose of it all

Deliberate practice is how we try to answer these questions in the workshop. You try to do it and see what you observe. Think about it, get feedback, and incorporate it into future tryouts. The goal is to create a framework for these experiments, one that people can use whenever doing testing activities to find out more about their reflection process.

I think that it is when reflection turns into habit that it becomes more powerful and revealing. My hypothesis is that after you acquire this habit, the freedom to find your own solutions or suggestions to improving your skills becomes truly visible, because at that point you don’t need to focus any more on how you reflect, which means you can give full attention to the object of your reflection.

I am not sure that this habit can be fully established within the duration of a workshop, but I noticed a key thing, which may or may not surprise you: habits have a starting point!

Ok…most probably this did not surprise you. But what may be surprising is that this starting point is sometimes all one person needs, and the most difficult step. I encourage you to take it, during this workshop or outside of it, because from my experience, no one else can take it for you.

I mentioned at the beginning of this article that a good motivation for me to work on observing my skills was the deadline of a presentation. However, although I used the opportunities of presenting as first steps in what I hope will be a long lasting habit, I think there is an underlying central reason which kept me doing this: I see my and your testing skills as a significant tool in problem solving, one that we use every day. They are the powerful heuristics which define how our work is performed. What ultimately motivates me is the belief that reflection upon our skills is a significant source of feedback that we can use to adapt and to grow. And I also like having fun with other people curious about testing and skills.

Let’s see what happens!